At the end of February, US President Donald Trump announced his intention to impose a 20% tariff on imports from the European Union and a 25% tariff on cars and other goods, including steel and aluminium from the old continent. Brussels responded with counter measures to address the US threat. Trump rejected Brussels’ proposal for mutual elimination of tariffs on cars and industrial goods, making it clear that the only way to reach a tariff truce would be for Europe to purchase $350 billion worth of American energy, primarily liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Today, 50% of Europe’s LNG already comes from the United States. Europe had already independently turned to the US to replace Russian gas, even proposing, in the Affordable Energy Action Plan, a mechanism for aggregating European demand.

Why this imposition from the American administration? Wouldn’t it be enough to leave the market, already inclined towards transatlantic LNG purchases, and to define quantities and prices in the mutual interest of the parties?

The imposition of tariffs is part of a negotiation strategy aimed at strengthening the US trade balance with various counterparts, Europe included.

The trade balance

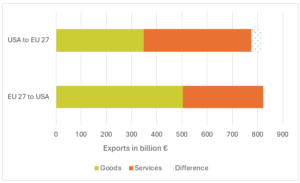

Yet the trade balance in goods and services between the US and Europe is only slightly in Europe’s favour—by 3% in 2023. It does not appear to be an imbalance severe enough to justify a trade war.

US-EU trade balance (2023)

Source: Eurostat

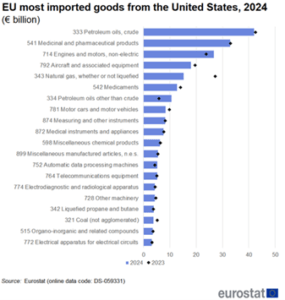

Looking in more detail at goods, however, over 50% of American commercial exports to Europe consist of fossil fuel-based products, fuels or end-use technologies: crude oil, petroleum products, engines, aviation and gas. These are sectors highly exposed to the climate transition underpinned by global agreements such as the Paris Agreement, from which the Republican administration seeks to withdraw.

Goods and services most imported by the EU from the US (2023–2024)

From this point of view, the confrontation initiated by the US goes well beyond gas imports. A significant part of the US administration’s negotiating objective can therefore be seen as an attempt to undermine the European Green Deal.

Why is the Green Deal a threat to Trump?

In fact, the Green Deal represents a serious threat to those American sectors that are most active in exporting to Europe and that supported Trump’s election campaign. Through the Green Deal, Europe is building its independence, energy security and competitiveness by progressively replacing its dependence on fossil fuels. In the EU electricity generation sector alone, fossil fuels dropped by a record 19% in 2023 while renewables rose to a record 44% share, with wind and solar being the main drivers: since the start of the Green Deal in 2019, they alone have avoided €59 billion in fossil fuel imports. This poses a risk of disadvantaging the United States compared to emerging countries that are establishing themselves in transition technologies.

The objective, therefore, is not only to “buy gas to reduce the trade imbalance” but to force long-term purchases that would prevent Europe from building its own energy independence and competitiveness, including through new suppliers in global markets. The same logic applies to end-use fossil fuel technologies, such as the automotive sector. The European Commission’s car regulation is interpreted, under false pretences, as a set of market-restricting regulations that justify the US imposition of tariffs. The EU’s decarbonisation objectives in the automotive sector, in fact, progressively exclude traditional cars and shift the European electric car market from a luxury product dominated by Tesla to a mass-market segment in which the US is weaker than both China and the European industry, which is supported by EU policies.

Between the US and the EU there is China

It was already clear during the Biden Administration that China was the primary rival. Today, both the instruments and underlying interests have changed. The Biden Administration’s strategy, summarised by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), aimed to challenge China by strengthening the US position in transition technologies within domestic and global markets. By contrast, Trump’s strategy can be interpreted as not allowing, through the imposition of trade tariffs, the implementation of climate policies by imposing their traditional fossil fuel-based goods on global markets.

In this context, the tariff negotiations could be interpreted as follows: while energy—and particularly LNG—is indeed part of the discussion, it is not the primary concern of the Trump Administration. The main objective is to prevent Europe, in light of the US’ choice to abandon decarbonisation targets, from turning to other suppliers—primarily China.

Italy and the role of gas in negotiations with Trump

At the national level, the Italian government has announced a €25 billion package to support businesses in response to the crisis and in view of negotiations. Of these €25 billion, 14 billion would be covered through the revision of the NRRP (National Recovery and Resilience Plan) “to support employment and increase productivity efficiency”; 11 billion through the revision of the cohesion policy approved last week by the Commission, which “may be reprogrammed in favour of businesses, workers and sectors most affected.” According to the Government, an additional 7 billion could be added to this through the Social Climate Fund, “to reduce energy costs for households and micro-enterprises through measures to compensate for logistical costs and incentivise clean technologies.”

In the Action Plan for Italian exports, the government proposes, as part of the negotiations, to increase European imports of LNG and military equipment from the US as a strategy to rebalance the trade relationship between the two countries. According to the Minister for Enterprises and Made in Italy, Urso, Italy could propose a request to extend the NRRP deadlines and a relaxation of Green Deal policies.

Meloni meets Trump

On 17 April, Giorgia Meloni will be received at the White House by Donald Trump. Energy is likely to feature in her European mandate, with gas as a potential bargaining chip.

From the European side, however, according to Energy Commissioner Jørgensen, while there is a clear interest in purchasing American LNG, there is no intention to compromise on the Green Deal.

In fact, the Trump Administration’s aggressive strategy has further demonstrated that, for Europe, the Green Deal is not merely a decarbonisation policy but the cornerstone of its security, energy independence and competitiveness—especially for a continent poor in fossil fuels and intent on building the growth of its internal market on green innovation.

In this context, it will be important to observe how effectively Italy can defend the Green Deal as a measure of European autonomy and climate policy—essential tools to boost industrial competitiveness through new investment in processes and products, enhance the continent’s energy autonomy, and protect citizens, businesses and public spending from the growing impacts of climate change.

How much more LNG can Italy and Europe import, and what are the implications?

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the US has played a crucial role in replacing Russian gas, becoming Europe’s top LNG supplier. In 2024, EU LNG imports exceeded 100 billion cubic metres. The US accounted for nearly half (45.5%) of these imports. In Italy’s case, the US was the second-largest LNG supplier in 2024, with a 34.5% share, behind Qatar (43.6%) and ahead of Algeria (14.8%).

In recent years, the US has become the world’s largest LNG exporter, surpassing Qatar in installed export capacity. Under the Trump Administration, the US has returned to the “drill, baby, drill” strategy, which aims to increase hydrocarbon production to boost exports to European and Asian markets, including through taxation.

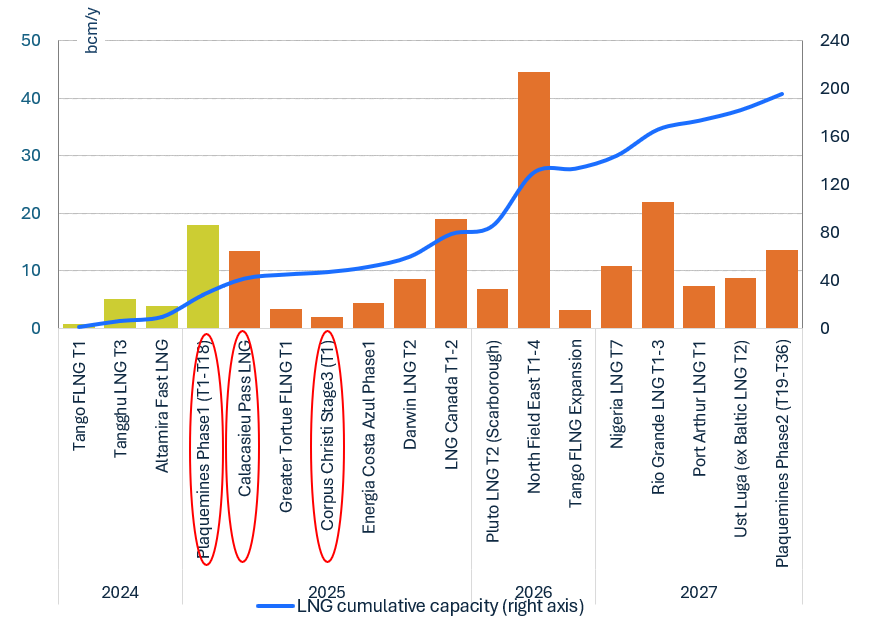

With the cancellation of Biden’s moratorium—which had suspended approvals for new LNG export requests, both pending and future—funding for LNG liquefaction and export terminals has resumed, leading to projected capacity increases over the next few years.

On the supply side, to date, US LNG export terminals have a capacity of 85 million tonnes per year, equal to approximately 117 billion cubic metres per year. By 2025, infrastructure expansion is expected to increase capacity by 26%. These additions will drive global LNG supply growth in 2025, adding nearly 30 billion cubic metres annually. These estimates suggest that by 2027, the US could account for about 70% of global LNG export capacity. However, as many projects originally planned for this year are experiencing significant delays in authorisation and construction, the deployment of new liquefaction capacity could be postponed until 2026.

Global LNG liquefaction capacity currently under construction (US terminals in red)

In terms of demand, Europe currently consumes around 450 billion cubic metres of gas per year, with 115 billion cubic metres supplied via LNG (2024 data). This includes 22 billion from Russia and roughly 50 billion from the US.

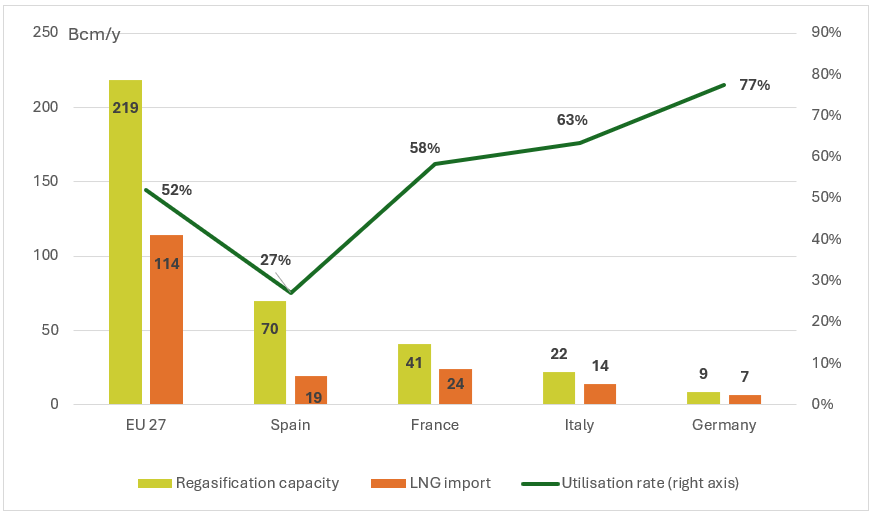

Europe’s current regasification capacity stands at 220 billion cubic metres per year. About 50 billion cubic metres/year of new capacity is under construction, expected to become operational by 2027. Of this, around 60 billion cubic metres/year—about 30%—is already contracted under long-term agreements, while the remaining 70% is allocated to the spot market. LNG infrastructure, whose gas is normally sold at a higher cost than pipeline delivery, represents an infrastructure for the flexibility of the European market. The average utilisation rate in 2024 was only just over 50%. A significant part of this infrastructure (70 billion cubic metres/year) is installed in Spain which, however, lacks strong integration with the broader European gas network and records usage rates below 30%.

EU regasification capacity and LNG imports (2024)

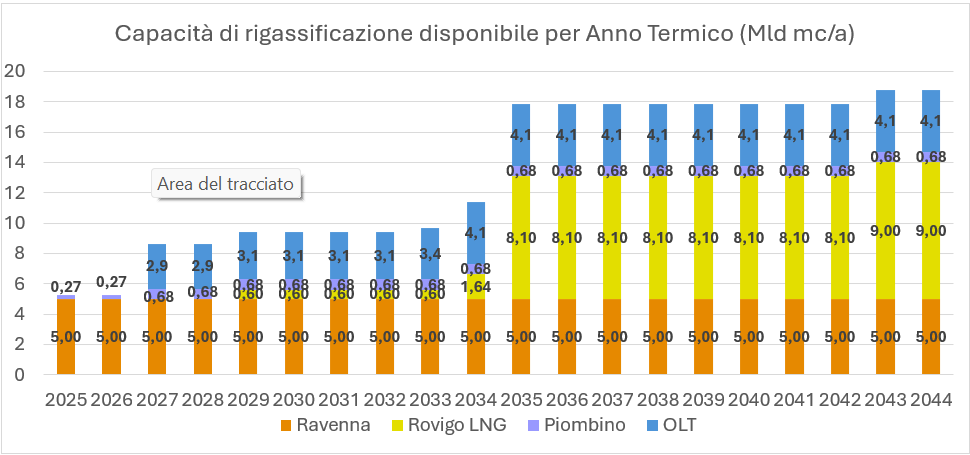

As for Italy, considering contracted capacity at existing regasification terminals (Rovigo-Cavarzere, Piombino, OLT Livorno, Panigaglia) and those coming into operation (Ravenna), the available capacity is:

- 5 billion cubic metres/year from the Ravenna regasification terminal, starting commercial operations in May 2025 with upcoming LNG allocation auctions.

- Around 1 billion cubic metres/year of unallocated capacity at the Rovigo regasification terminal from 2029 to 2034, and about 8 billion/year from 2035 onwards.

- Potentially 4.3 billion/year from the Piombino regasification terminal until 2043.

- Around 3 bcm/y from Olt Livorno regasification terminal from 2027 to 2033, and around 4 bcm/y from 2034 to 2044.

This results in the following unallocated LNG import capacity available to accommodate US LNG exports over the years:

While there is some available capacity in existing regasification terminals, it is unclear why a forced long-term purchase would be in the buyer’s interest, when open-market LNG allocation auctions would allow for the selection of quantities, prices, and deliveries to be defined by the meeting of the parties.

Binding regasification capacity into long-term contracts reduces infrastructure flexibility, increases supply risks (especially from a country not hesitating to use trade wars as a geopolitical tool), may impose non-market-defined costs—aggravated by take-or-pay characteristics typical of gas contracts—and exposes Italy to volume risks, potentially undermining other contracts with suppliers that have provided us with gas during the Russian crisis.

On the other hand, further expanding Italy’s regasification capacity would make little sense. European and Italian gas demand has fallen by 18% over the last three years, from 76 billion cubic metres in 2021 to under 62 billion in 2024. Our study “The state of gas” shows that existing infrastructure is sufficient to ensure supply security, thanks to flows from Algeria, Azerbaijan, Libya, domestic production and existing regasification capacity. New investments would impose further costs on infrastructure undergoing transition. The rise of renewable energy in electricity markets, the electrification of household consumption, energy savings and efficiency, and a decline in industrial production (largely due to gas prices) all point to a long-term decline in gas demand in the European market, increasing infrastructure costs for end users.

While the data suggest that Italy and Europe could consider purchasing more US LNG, which was already naturally happening in the market, this should not come in response to what amounts to strategic pressure from the United States, which goes beyond the purchase of new LNG. The objective of the US appears to be to dismantle the European Green Deal through a forced realignment of the transatlantic relationship around fossil fuels, deterring Europe from turning to new suppliers of clean energy in global markets, such as China.

Today, the Green Deal represents a strategic lever to enhance European and Italian competitiveness, promoting innovation in production processes, products and energy efficiency. Choosing to hinder the Green Deal means clinging to outdated fossil fuel-based economic models and aligning with Trump’s policies, which transparently seek to protect only partisan interests. A dependence on US fossil fuels risks obstructing the EU’s effort to build sustainable new value chains, ignoring shifting global market dynamics in which it is unthinkable to exclude China. Such a choice would ultimately harm Italian businesses—already burdened by high gas costs—and exclude them from the opportunities offered by a more sustainable and competitive economy.

Photo by David Dibert