On 24 July, to mark the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Brussels and Beijing, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Council President António Costa travelled to the Chinese capital for the EU-China Summit.

Originally set to take place in Brussels, the Summit was held at a time of growing uncertainty in EU–China relations. With the global economy shaken by Trump’s neo-protectionist measures, Europe finds itself more than ever in need of keeping dialogue with China open, especially on climate and decarbonisation technologies. In this context, Brussels’ approach to Beijing is key in defining Europe’s global positioning.

In Europe’s balancing act with China, the Trump factor plays a key role. The scenario created by the US administration’s policies against the energy transition and its reluctance to cooperate with Beijing is prompting European institutions and Member States to assess which areas of cooperation with China should remain active, where new avenues might be opened, and where sacrifices are necessary.

Against this backdrop, expectations for the Summit were limited, partly due to the Commission’s repeatedly emphasis on existing geopolitical differences with China. The meeting concluded with the publication of a joint statement on climate cooperation and several statements by Commission President von der Leyen that underlined both the risks and the opportunities embedded in the EU-China relationship.

China between coal and renewables: a new climate leader?

When it comes to tackling global decarbonisation, engagement with China is essential. The country plays a pivotal role in the energy transition, largely driven by the consistent overproduction of clean technologies by Chinese companies, which not only promotes exports to Europe but also the evolution of China’s domestic market and the complex decarbonisation of the country.

In recent years, China has exponentially increased its renewable energy generation installations, particularly wind and solar. Amid growing energy demand, the country continues to expand its overall energy capacity. In 2024, for instance, 86% of new installed capacity came from renewable sources. By 2025, renewables accounted for 56.4% of total installed capacity, and one third of the electricity produced in China now comes from renewable sources.

Thanks in part to these efforts, China’s greenhouse gas emissions have seen a significant improvement in recent years. Notably, in 2024, CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels and cement fell by 1% compared to the previous year for the first time, despite continued economic growth and rising energy demand. This represents a historic achievement for China, which had previously pledged to peak its emissions by 2030.

Nonetheless, while encouraging, these results do not yet guarantee the fulfilment of the targets set out in Beijing’s NDC. China remains the world’s largest CO₂ emitter, responsible for 25.37% of global emissions (2022), with per capita emissions at 8.4 tonnes annually. This figure is higher than the EU average and just over half that of the US.

Looking at the source of Chinese emissions, nearly 85% stem from energy production, driven by coal, which still accounts for more than 60% of the national energy mix (2023). The widespread use of coal as an energy source remains a negative aspect of China’s energy and climate trends. Though the share of new installed coal capacity has declined in relative terms in recent years, the absolute figure continues to rise, reaching 1,190 GW in 2024 (still below the 1,889 GW derived from renewable sources).

Beijing continues to invest in new coal plants to stabilise its energy system, meet peak demand, and pursue strategic energy autonomy in the absence of domestic oil and gas reserves. However, this trend must be reversed if China is to stay on course to meet its stated goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2060, as outlined in its 2020 “Low Greenhouse Gas Emission Development Strategy.” While the 2060 carbon neutrality target allows China flexibility in choosing different emission reduction pathways, the commitments made so far remain insufficient to align with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

However, emissions must be viewed in the context of the high proportion of Chinese-made goods consumed in Europe and worldwide. To account for this, consumption-based emissions should be taken into consideration, calculated as domestic emissions minus those generated by the production of goods and services exported to other countries, plus the emissions linked to the production of imported goods and services. When viewed through this lens, China’s per capita emissions fall to 7.2 tonnes of CO2 (2022) – a figure that is lower than both the US and the EU.

In conclusion, while China remains the world’s top CO₂ emitter in absolute terms, a share of these emissions reflects its role as the “world’s factory” and is therefore partly attributable to the Western consumerist model – given that many of these goods are ultimately exported elsewhere. It is true, as we have seen, that China continues to invest in coal. However, this does not detract from the fact that it is also building nearly twice as many renewable energy plants as the rest of the world and exporting the very technologies that enable the energy transition of entire continents, Europe in particular.

EU–China and the Chinese decarbonisation model

China’s clean tech industry currently dominates the global market share, including in Europe. Beijing’s leadership has slowly built this market control through massive investment starting in the late 2000s, facilitated by low labour and capital costs, as well as policy consistency. This has allowed Chinese firms to have such overproduction capacity that they can export low-cost technologies, quickly absorbing market shares previously controlled by European companies. This is particularly true for the production of photovoltaic panels, where China now controls 80% of global production. At the same time, Chinese automotive giants such as BYD are expanding their presence across Europe and globally. As such, issues related to industry and sustainability markets must remain central to the EU-China dialogue.

For the EU, the key challenge is to strike a balance between protecting the competitiveness of European companies and meeting its emission reduction targets, along with the continent’s broader path towards decarbonisation by 2050, for which the import of clean technologies from China remains essential.

As von der Leyen also highlighted in her pre-Summit statements, concerns about the competitiveness of European companies are closely linked to the risk of creating new dependencies on the supply of minerals and technologies essential for renewable energy generation. These energy-related dependencies raise fears of potential geopolitical leverage, echoing the experience of many EU countries, including Italy, with their past reliance on Russian gas.

However, it is important to specify that we are referring to imports of materials that, by their very nature, follow different dynamics from those of oil and gas flows. Importing technologies such as solar panels, which have a life cycle of over 20 years, entails lower risks in terms of potential dependencies – risks that tend to stabilise and even decline over the long-term, partly thanks to recycling. Furthermore, to ensure the competitiveness of its companies, the EU must in any case pursue policies to strengthen, in the medium to long-term, those clean tech sectors where Europe still holds global market shares. Investment in innovation will also be essential to support the energy transition through an industrial transition strategy.

In this context, the EU’s strategic approach should pay close attention to the potential cybersecurity risks associated with importing technology from China and maintaining these systems. In the case of both solar and wind power, modern installations process ever-increasing amounts of data, the remote management of which by China could make European energy systems more vulnerable to cyber attacks.

Italy–China relations

Within this framework of Sino-European relations, Italy can operate in a context of historically established bilateral ties, where it has consistently played a significant role as a bridge between the West and the East.

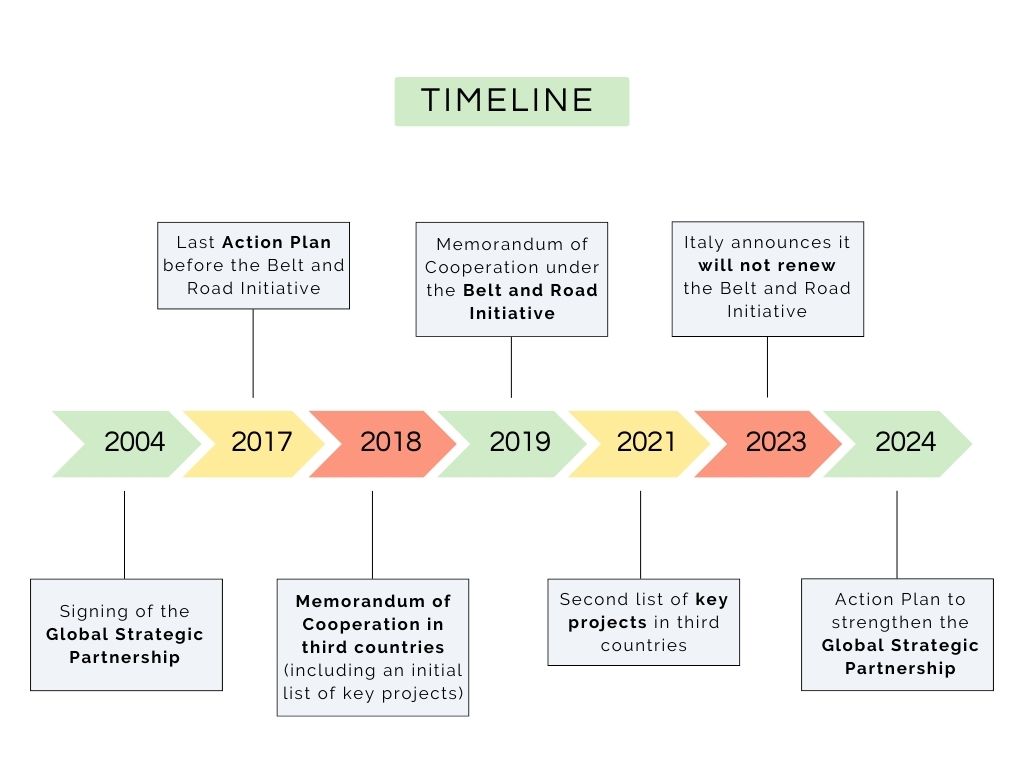

In 2019, following the European wave of rapprochement with China and the strengthening of diplomatic relations that began in 2015, Italy became the first and only G7 country to sign a cooperation agreement under the Belt and Road Initiative, aiming to intensify bilateral economic exchanges, even at the cost of diverging from the EU’s common position. However, the agreement has suffered from poor implementation in subsequent years, partly due to the outbreak of the pandemic, and therefore has not achieved the desired objectives in terms of investment in infrastructure development.

In the years that followed, a general feeling of scepticism and caution towards interactions with Beijing spread within the EU. This was linked both to pandemic developments and concerns about potential dependencies on Chinese imports, prompting the formulation of a de-risking strategy to reduce the European market’s vulnerability. This widespread sentiment, coupled with a lack of significant macroeconomic results and a desire to renew ties with the US, led the Meloni government not to renew the agreement at the end of 2023. The Trump administration, however, is now pushing Italy towards a more intense decoupling from China, as stated by the new US Ambassador to Italy in his hearing before the US Senate.

The non-renewal of the agreement does not seem to have negatively affected Italian relations with Beijing: in 2024, the Meloni government, through presidential and ministerial visits, has intensified its contacts with China in an effort to revive the trade partnership outside the context of the Belt and Road Initiative. The number of reciprocal diplomatic visits between Rome and Beijing increased in 2024 compared to the pre-pandemic period; the heads of state maintain an important relationship, as evidenced by Mattarella’s visit in 2024, and the two countries sustain stable cultural exchanges.

Among the signs of a renewed bilateral partnership, the 2024-2027 Action Plan has revitalised the Global Strategic Partnership signed between Italy and China in 2004. The Plan focuses on numerous areas, including economic and trade cooperation, with particular emphasis on rebalancing trade – a necessity in line with the European Commission’s priorities for EU-China relations.

Regarding green and sustainable development, the 2024-2027 Plan highlights support for the Paris Agreement goals, the implementation of the COP28 outcomes, and coordination on the supply of critical materials and clean technologies.

The Plan also emphasises collaboration with third countries – an area of cooperation based on a previous bilateral agreement signed in 2018, which so far has primarily encouraged investments by Italian and Chinese companies in Africa and Central Asia.

Thanks also to the international momentum of the Meloni government, stable and constructive relations with Beijing and the existing institutional framework, Rome appears to be well-positioned to lead a new cooperative approach in Europe-China relations. With a view to a desirable new era of Sino-European relations based on predictability and reliability, Italy can and must therefore promote the path of “selective cooperation” between the EU and China, based on shared standards and the principle of reciprocity in strategic sectors where a mutually beneficial scenario can be built. Beijing remains an indispensable partner on climate, trade and the energy transition, and a common European position defining when and how to cooperate with China is necessary for the competitiveness of European businesses and the credibility of climate goals.

This is why Rome should not miss the opportunity to take part in the process of redefining relations between the two blocs, which will have a fundamental impact on broader global geoeconomic balances.

The EU-China Summit of 24 July: expectations and outcomes compared

In her speech to the European Parliament ahead of the EU-China Summit, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen adopted an ambivalent tone regarding Beijing. While von der Leyen was explicitly open and willing to cooperate with China to achieve decarbonisation goals, she did not hold back criticism of Beijing’s foreign policy choices (Chinese support for Russia and its implications for the war in Ukraine) and economic policy (government subsidies to clean tech companies flooding the EU market with low-cost products).

Pre-summit hopes were focused on achieving alignment around climate multilateralism, which could bring Brussels and Beijing closer during discussions and serve as the foundation for the entire dialogue process. With the (new) US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, both the EU and China find themselves in the position – and with the necessity – to shape the future of multilateral climate cooperation. Ahead of COP30 and COP31, and considering the imminent announcements of updated NDCs that will update each bloc’s emission reduction targets, it was crucial for Brussels and Beijing to act as guardians of the Paris Agreement.

Indeed, this was achieved. Climate and environment dialogues were positive and led to, at the conclusion of the Summit, the publication of a joint statement promoting shared leadership in supporting a just energy transition. The document lists six priority commitments for EU-China cooperation, including enhancing efforts on adaptation, managing and controlling methane emissions, establishing carbon markets, and facilitating access to renewable energy and clean technologies, including for developing countries. In this context, the statement represents a positive commitment by both parties to support the process initiated by the Paris Agreement, the implementation of COP outcomes and the global energy transition.

From a commercial perspective, Brussels also entered the Summit keen to address more pressing bilateral issues, including subsidies for Chinese electric vehicle production and the resulting EU tariffs, controls on exports of critical materials and Beijing’s financing of clean tech production. These issues, in particular, contribute to the phenomenon of net-zero product dumping, a practice investigated by EU institutions regarding EVs due to its impact on European companies’ competitiveness.

Trade with China in energy transition technologies presents a strategic dilemma for the EU. While integration with the Chinese market and the purchase of low-cost technologies would enable the Union to accelerate its decarbonisation, this comes with significant challenges. The focus on the competitiveness of European industry and the EU’s economic sovereignty, which has grown stronger during von der Leyen’s second term, requires a careful balance between importing affordable Chinese technologies (solar panels and EVs in particular) and protecting EU companies. Accordingly, the EU and its Member States approached the 24 July Summit seeking compromises, in line with the recent de-risking approach from China advanced by the Commission itself, which aims to maintain dialogue and trade flows without compromising the safeguarding of European industries.

All these themes were addressed during the Summit, showing willingness and readiness to engage in dialogue, but also highlighting the gap that remains between the two sides. In her post-Summit remarks, von der Leyen expressed moderate satisfaction with the signals sent by the Chinese leadership about resolving trade disputes.

Regarding Chinese subsidies for clean tech production, the EU leader’s statements mention that Chinese leadership has acknowledged the problem and expressed a willingness to redirect subsidies from production toward the consumption of these technologies.

To resolve disruptions in the flow of critical materials from China to the EU, both parties agreed to establish a mechanism to address bottlenecks in these supply chains.

Outstanding questions in EU-China relations

The Summit confirmed existing expectations and doubts about the future trajectory of relations between Europe and China, offering grounds for optimism particularly on multilateral climate cooperation, but without providing definitive answers to resolve the most contentious trade and competitiveness issues. The course of future discussions and mutual strategies on this topic will continue to shape the trajectory of relations between the two blocs.

While waiting to see how the relationship between Brussels and Beijing will continue to unfold, questions remain about the EU’s and Italy’s approach, in particular, to dialogue with China.

Will the EU and China succeed in acting as guardians to preserve multilateral climate cooperation? Will the process initiated at the Summit prevent US pressure to reduce engagement with Beijing from hindering EU-China relations and Europe’s decarbonisation efforts? Will the EU find a way to pursue selective cooperation with China, or will fundamental geopolitical and trade disagreements overshadow willingness to collaborate? And finally, regarding Italy: will Rome be able to play a significant role in the ongoing redefinition of relations between the two blocs, particularly on the green agenda?