As NATO countries debate how to meet the new target of allocating 5% of GDP to defence and security, the climate crisis is splitting Italy in two: extreme temperatures in the south, potentially reaching 50°C – levels never before recorded in Europe – and severe weather events in the north. While the intensification of armed conflicts has reignited the debate around rearmament, unconventional threats are also emerging, redefining the very concept of security. The climate crisis, with its systemic and cross-cutting impacts, already represents one of the main threats to Italy’s economic and social life, and is a major driver of global instability. Without swift action, climate change is set to become the single biggest threat facing the planet, as Ana Toni, Executive Director of COP30, recently warned. In this context, it is both timely and essential to adopt a broader understanding of the threats countries must defend themselves against, one that fully incorporates ‘climate security.’

Uncertainties surrounding European rearmament

In recent years, the world has witnessed a significant intensification of armed conflicts, the most serious since the end of the Second World War. This has fuelled an unprecedented rise in global military spending, which in 2024 exceeded $2.7 trillion. Against this backdrop came the Hague Summit Declaration, proposing a new NATO target: by 2035, members should allocate 5% of their GDP to defence and security, split into 3.5% for traditional military spending and 1.5% for broader security measures.

This marks a significant shift, driven in large part by the Trump administration. Alongside policies such as the tariff wars, it forms part of a broader foreign policy strategy aimed at protecting America’s geopolitical and geoeconomic position in a rapidly changing world order. In this context, Europe is being called upon to defend its interests, its vision and its international role. While on the trade war front, the European response can and must rely on the Green Deal as a tool to defend its independence and competitiveness, on the issue of rearmament, Europe appears more vulnerable.

Despite the existence of EU security and defence mechanisms, many experts highlight structural weaknesses that a simple increase in military spending is unlikely to resolve. In addition to the absence of a unified European army, there is still no shared foreign policy agenda among Member States, who often take vastly different positions on fundamental issues.

Furthermore, recent estimates warn that meeting the 5% target could affect the EU’s credit ratings and undermine efforts to restore public finances in several countries, including Italy. While the European Commission has put forward solutions to ease budgetary constraints – such as the Readiness 2030 plan with €800 billion in additional defence investments, the SAFE investment programme, the European Defence Industry Programme (EDIF) and a proposal to establish a European rearmament bank – a fundamental question remains: which priorities are at risk of being sacrificed?

It is fair to ask whether the current shift in budget priorities towards defence could erode the fiscal space available for other strategic and security priorities, such as climate action, diverting resources away from domestic decarbonisation and adaptation policies and international climate cooperation.

There is also the additional concern of greenhouse gas emissions. According to CEOBOS, the global military sector is responsible for over 5.5% of global emissions. A further increase in military expenditure could therefore exacerbate the climate crisis. The same report highlights the exceptional emissions produced by armed conflicts: for instance, emissions generated during the first 120 days of the Israel-Hamas war are estimated to have exceeded the annual emissions of 26 countries.

“Our biggest war” – what if the real war is against the climate?

While wars and the arms industry contribute to intensifying the climate crisis, the impacts of climate change can, in turn, exacerbate existing conflicts or give rise to new ones.

Ana Toni, CEO of COP30 in Belém, has firmly stated that climate change poses the greatest threat to global security – “our biggest war” – warning that no amount of military spending will suffice to manage the conflicts climate change will unleash unless urgent action is taken with strategic vision.

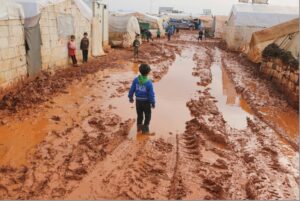

Climate change acts as a threat multiplier, especially in fragile regions. In strategically significant areas for Italy and Europe, such as the broader Mediterranean and Africa, rising temperatures, drought, sea-level rise and extreme events are undermining water and food security, threatening socio-economic stability and fuelling political tensions. There is no shortage of concrete examples. In Syria, the extreme drought from 2006–2010 devastated agriculture and forced thousands to migrate to cities – a dynamic many analysts believe contributed to the socio-economic tensions that led to the uprising and 2011 civil war. In sub-Saharan Africa, dwindling resources have intensified clashes between nomadic herders and resident farmers. In Mozambique, recurring cyclones have driven instability, internal migration and armed violence.

Extreme weather events can destabilise already fragile governments, drain public funds and compromise essential services such as healthcare, education and security – creating a vicious cycle of poverty, mistrust and radicalisation.

This link between climate and security is now widely acknowledged. Many actors are beginning to integrate it into their strategies. Notable examples include: the first US National Intelligence Estimate (2021), France’s Climate and Defence Strategy (2022), Germany’s Climate Foreign Policy (2023) and the EU’s Climate and Defence Roadmap. NATO included climate change in its 2022 Strategic Concept and established the NATO Climate Change and Security Centre of Excellence (CCASCOE) in 2024. The African Union Peace and Security Council recently published the Africa Climate Security Risk Assessment – Addressing the Impacts of Climate Change on Peace and Security across the African Continent.

Against this backdrop, Italy remains a notable absentee. Despite its strategic position in the Mediterranean – a nexus of migration routes, a climate hotspot and a region of geopolitical tension – the country lacks a foreign policy framework that systematically incorporates climate risks.

Investing in a safer future

Political awareness of the link between climate and security is growing, but practical implementation remains inadequate. The gap between ambition and reality is particularly evident in financial terms. While declarations of intent multiply, actual resources to tackle the climate crisis remain limited.

Investing in climate security means not only preventing future losses and damage but also reducing conflict and forced displacement. Lowering emissions, strengthening the resilience of vulnerable communities and supporting fragile countries to adapt and recover are ways to neutralise future threats at their roots. Doing so requires a mobilisation of finance on both a European scale (for domestic needs) and a global one – running into the trillions.

The recent Conference on Financing for Development in Seville showed just how insufficient the global response remains. Declining official development assistance (ODA) for the most vulnerable countries, coupled with soaring military expenditure, demands urgent reflection on global priorities.

A study by ODI Global examined NATO and OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) countries’ commitments to spend 2% of GDP on defence and 0.7% of gross national income (GNI) on development aid. While defence spending has consistently exceeded the 2% benchmark, development aid remains well below 0.7%. Between 2018 and 2023, military budgets grew by an average of 65%, while from 2024 onwards, planned cuts to ODA could shrink aid volumes by 31% by 2029.

The United States, once the world’s largest donor, accounting for 30% of global aid, has dismantled USAID and cancelled over $75 billion in programmes. Other donors, including Canada, New Zealand, Austria and several EU countries, have also announced cuts. The UK justified its reductions as necessary to boost defence spending.

The European budget is also being restructured. Although the proposed Multiannual Financial Framework (2028–2034) includes a net increase in funding for external action, nearly all funds are to be merged into a single instrument – Global Europe – with no minimum allocation guaranteed for development. While designed for flexibility, there are fears this could lead to funds being diverted towards short-term priorities at the expense of long-term cooperation.

Meanwhile, the United Nations system is also under pressure, facing potential staff cuts, agency mergers and structural streamlining. This comes at a time when strengthened multilateral governance is most urgently needed, through coordination between security, development and climate agendas.

In this scenario, we must ask: what kind of investment truly guarantees global security? Is it realistic to believe that increased military spending can address growing geopolitical fragmentation and the erosion of multilateralism? Or would it be more effective to prioritise cooperation, resilience and climate security?

Security for Italy

Italy has both the opportunity and responsibility to chart a different course. In line with its international ambitions and the objectives of the Mattei Plan for Africa, in 2024 Italy increased its contribution to the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) by 25%. According to OECD data, Italian development aid rose by 6.7% over the previous year, against a global decline of 7.1%. This is a positive sign, though still far short of the international target of 0.7% of GNI. In 2024, Italy stood at 0.28%.

On the defence front, Italy spent around 1.5% of GDP in the same year and expressed its intention to gradually reach NATO’s 5% target by 2035, in line with budget constraints. To do so, it plans to include previously excluded categories, such as the Coast Guard, Guardia di Finanza, cybersecurity and controversially, infrastructure like the Strait of Messina bridge, if considered strategic.

Recognising that security today extends far beyond the military dimension alone, encompassing climate, social and economic aspects, compels us to urgently redefine national priorities. The idea underpinning these proposals could serve as a starting point for reflecting on what security means for Italy today. It is a matter of giving real substance to the concept of climate security, integrating it into both domestic policy and Italy’s international engagement, particularly in the Mediterranean and Africa.

Recommendations

To tackle the interconnected challenges of our time, we must move beyond a narrow view of security and adopt an integrated approach, one that recognises climate change as a systemic threat to global stability.

- The international community should prioritise a concept of security capable of responding to the multiple, interconnected challenges of the modern era, placing the climate dimension at its core. Climate-related risks, in terms of economic and human losses and instability, must be recognised as a strategic priority. In this context, climate cooperation can serve as a bridge between opposing geopolitical blocs, helping to ease tensions and strengthen multilateral dialogue.

- The European Union should ensure that increases in defence spending do not come at the expense of the Green Deal. Any increase should be matched by equivalent investments in climate projects, particularly in adaptation and resilient infrastructure.

- Italy should adopt a national strategy on climate and security, integrating climate risk analysis into its foreign policy, cooperation and internal security. The NATO-designated 1.5% of GDP for broader security should be used to strengthen the resilience of territories and communities through investments in critical resilient infrastructure, adaptation measures and land protection.

- In foreign policy, both the Mattei Plan and the Rome Process should focus on structural investments in climate resilience in partner countries, promoting shared development pathways that take into account the direct and indirect impacts of the climate crisis. The energy transition must become the cornerstone of new models of economic cooperation. Italy can play a leading role in promoting regional energy integration across the Mediterranean, supporting initiatives such as TeraMed and facilitating the transfer of technologies and expertise.

- To strengthen public policy coherence, it is urgent to establish an interministerial task force to coordinate initiatives in foreign affairs, defence, development cooperation and the environment, ensuring alignment with the climate objectives of the Paris Agreement. This structure should be supported by permanent working groups bringing together experts, civil society and the private sector to monitor climate risks and update policy tools. The armed forces could also play a greater role in managing climate-related risks and emergencies, through the establishment of centres of excellence for climate risk analysis and the creation of specialised units to be activated when needed.

Photo by Jannik