What is an NDC and what does it contain?

- Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are documents that outline the climate pledges of the Parties that signed the Paris Agreement. The sum of these commitments contributes to combatting climate change, while promoting sustainable development and poverty eradication. According to the 2015 Paris Agreement, Parties have a legally binding duty to present their NDCs every five years, with the aim of limiting the rise in global average temperatures to below 2 degrees and pursuing efforts to keep it under 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to preindustrial levels. This means that States and regional organisations, such as the EU, design their own NDCs and propose new climate pledges every five years.

- This year, Parties to the Agreement are due to submit their updated NDCs (NDC 3.0), with more ambitious targets for 2035. Being nationally determined, NDCs can present their quantified CO2 emission reduction targets either in terms of economy-wide absolute targets, which is required for developed countries, as well as targets relative to GDP or other economic indicators, which is more common for developing countries. At COP28, in the context of the Global Stocktake decision, all countries were encouraged to submit economy-wide, quantified emission reduction targets aligned with a 1.5 pathway, covering all GHGs. Notably, China has committed to include all GHGs and economic activities in its NDC 3.0, a step up from its previous NDC, which only set targets for carbon dioxide emissions and renewable energy deployment. Countries may propose, in their NDC, climate targets that are conditional on receiving international climate finance or/and unconditional targets that can only be achieved with domestic resources.

- NDCs may also include adaptation actions, which developing countries tend to include as a significant part of their contribution to global climate action. Developed countries, which are subject to more stringent reporting processes, tend to only report mitigation policies, though some report mitigation co-benefits of the adaptation actions they are planning. Parties also communicate detailed adaptation plans in a separate ‘Adaptation Communication’.

As contributions are nationally determined, how can the global community assess where it stands in terms of reaching the Paris Agreement objectives?

The Paris Agreement establishes a mechanism dedicated to this purpose, known as the Global Stocktake (Article 14, Paris Agreement). This is a process that takes place every five years, whereby the Parties assess collective progress towards reaching the Agreement’s objectives. The Global Stocktake that took place at COP28 in Dubai in 2023 highlighted that the world is off track to meet the Paris Agreement objectives, both on adaptation and mitigation, with an increasing gap in international climate finance for developing countries. However, it also found that without the NDCs, the world would be on a trajectory to a 4°C increase in average temperature, while current policies suggest a 2.1-2.8°C rise. Therefore, the COP global stocktake Decision (1/CMA.5) called for a boost in action, including a tripling of global renewable energy capacity, a doubling of the average annual energy efficiency rate, and, finally, a transition away from fossil fuels.

While the Conference of the Parties (CMA) has asked the Parties to submit the third revision of the Nationally Determined Contribution by February 2025, the UNFCCC Executive Secretariat has recognised the greater importance of strong, well-crafted NDCs, and stated that Parties must submit their NDCs by September at the latest to be included in the UNFCCC’s synthesis report. As per the so-called ‘ambition mechanism’ embedded in the Paris Agreement, the next NDC should include greater ambition than the current NDC. As of today, only 22 of the 195 Agreement Parties have submitted their NDCs to the UNFCCC, though this number is expected to grow significantly in the coming months.

What about the European Union’s NDC?

Among the NDCs to be presented at COP30 in Brazil, outlining objectives for 2035, is the EU’s NDC. The European Union participates in negotiations as a regional economic integration organisation (art. 20 Paris Agreement), after having agreed on a common position among its Member States by consensus. This means that Member States have a collective climate target defined through a joint NDC. The EU’s current NDC headline target is a net reduction of -55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. This overarching target is accompanied by legally binding sectoral policies to ensure its achievement. The most relevant policies adopted by the EU to reach its climate targets include the revision of the EU Emission Trading System (EU ETS), the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), and the Land Use, Land Change and Forestry Regulation (LULUCF). Complementary legislation includes the Energy Efficiency Directive, the Renewable Energy Directive, and all other pieces of legislation commonly grouped under the name ‘Fit for 55’. These policies cover all EU emissions and focus mainly on the energy, transport and buildings sectors, as well as on enhancing carbon sinks. Collectively, they contribute to reaching the -55% target by 2030. As the submission of the EU’s NDC to the UNFCCC is expected by September 2025, EU leaders will likely need to define the 2035 EU target over the summer, to be presented at COP30 in the autumn.

Does Italy have its own NDC?

Italy’s NDC is the EU’s NDC, since the EU signed the Paris Agreement as a regional economic integration organisation (art. 20 Paris Agreement). Consequently, all Member States agree on a common EU-wide target, which is then implemented domestically, usually over a ten year period, according to the Governance Regulation. The overarching EU target is then ‘distributed’ among Member States and to private entities operating in the EU (through the EU ETS). At the national level, these objectives are implemented through National Energy and Climate Plans. These provide an administrative framework to implement emission reduction commitments over for ten years. Since the NECPs derive from EU legislation and, in particular, from the Governance Regulation, the commitments made in NECPs should be aligned with the EU’s NDC. Therefore, NECPs must include Member State’s strategies to align with the EU’s collective target for 2030. Currently, while Italy’s NECP aligns with several EU objectives, such as renewable energy targets, it falls short in others, for example in emissions within non-EU ETS sectors such as the transport sector. In particular, Italy should reduce its emissions in non-EU ETS sectors by -43.7% by 2030 compared to 2005; however, based on existing policies included in the NECP, Italy will achieve a reduction of -40.6%.

Are we going to meet the 2030 targets at the European and Italian level?

The key policy tools for reaching the 2030 EU targets are the NECPs. The overall EU objective to reduce GHG emissions by -55% by 2030 compared to 1990 has been translated into legal form by the Fit for 55 package of directives and regulations, encompassing different sectors of the economy. The implementation and strategies to reach the objectives are then framed at the national level. Considering this multilevel governance structure, the most recent NECPs analyses suggest that the risk of not fully implementing the measures or reaching EU objectives at the national level remains, in particular with regard to sectoral policies. Even though several Fit for 55 measures have not yet been fully implemented within Member States, more could be done to reach the targets over the next five years. According to the EU’s first Biennial Transparency Report submitted to the UNFCCC in December, as the main transparency requirement under the Paris Agreement, as of 2022, the EU’s net greenhouse gas emissions had fallen by 31.8% since 1990. Preliminary data published in the Climate Action Progress Report shows a further reduction of 8% in 2023, which would represent a total reduction of 37% since 1990.

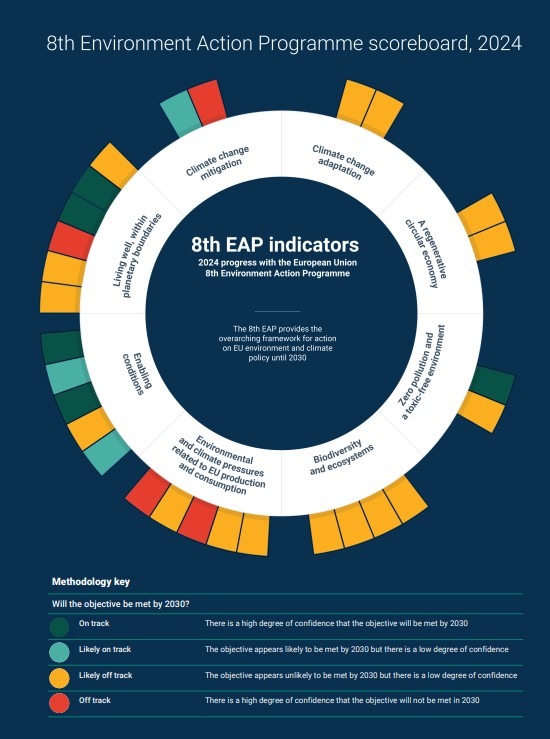

Moreover, a recent report by the European Environmental Agency states that the EU is likely to achieve a -49% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 but could still reach the -55% target with additional national measures. Despite this, even if the general objective is achievable, the trend of several indicators that are tailored to sectoral policies shows that current policies remain insufficient, and that there is no time to waste in implementing the European Green Deal.

What opportunities could an ambitious NDC bring for Italy and the EU?

By having an ambitious NDC, the EU would confirm the commitment it established under the European Climate Law, which enshrines the climate neutrality objective by 2050 into EU legislation. During the summer, the European Commission will amend the European Climate Law and propose a 2040 objective. The trajectory between 2030 and 2040 will be pivotal in defining the speed of the transition over the next decade. Having a 90% target with an ambitious trajectory for 2035 would strengthen the EU’s leadership in multilateral climate negotiations and increase its leverage to speed up climate action worldwide. Even if it is not necessary to legally define the 2040 objective to adopt the EU’s NDC, the two documents are connected and complementary. Having an ambitious target would also lead to economic benefits for the EU. Indeed, while implementing the Green Deal will not have major positive effects on GDP, it would prevent negative ones by significantly reducing costs and risks for the entire economic system to adapt to the increasingly adverse effects of climate change, as underlined by the European Central Bank.

At the national level, the latest ISPRA inventory report points to the fact that Italy has reduced emissions by 26.4% in 2023 compared to 1990 (excluding natural carbon sinks). By 2030, Italy plans to reduce its emissions by another 23% to reach a –49.4% reduction in emissions. If a 90% target by 2040 is agreed at the EU level, Italy would benefit from long-term political willingness to act on climate change policies, which will encourage investments and infrastructure planning.

Which are the most relevant NDCs at the global level? What is the role of complementary multilateral processes?

The countries that produce the majority of the world’s GHG emissions include China, the United States, the EU, India, Russia, Brazil, Indonesia, Canada and Japan. Their NDCs are therefore relevant to understanding whether the world is on track to reach the Paris Agreement’s objectives. All of these countries are members of the G20, therefore, action by this multilateral forum, which accounted for 84% of global electricity demand in 2024, significantly contributes to fostering climate pledges which address a large portion of global emissions. For example, the G20 plays a crucial role in committing the largest economies to implementing the Paris Agreement and scaling up climate finance: in the G20 context, Brazil organised the first Circle of Finance Ministers with the aim of mobilising 1.3 trillion dollars by 2035, building on the last summit which recognised the fundamental role of finance ministers in climate action. Notwithstanding these notable initiatives, G20 members’ pledges are still insufficient to limit the global average temperature to below 2 degrees.

What happens now that the United States has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement?

The Paris Agreement was structured in a way that excluded the possibility of sanctions in the case of non-compliance or withdrawal from the Agreement (art. 28). While submitting NDCs is legally binding, the Paris Agreement encourages a bottom-up approach to climate policies, fostering multilateral trust and international cooperation. By leaving the Paris Agreement for the second time, the US confirmed the Trump administration’s lack of engagement in multilateral processes. The US withdrawal is also consistent with Trump’s strategy on tariffs, which implies forcing long-term purchases that would prevent other countries, such as European ones, from building their own energy independence and competitiveness, including through new suppliers in global markets. Despite the choices of the federal administration, concretely in terms of the achievement of climate goals, it has to be highlighted that 24 US States have committed to uphold the goals of the Paris Agreement and implement climate targets. Consequently, domestically, a large part of US climate policies are still in place. At the international level, while the US has renounced a climate leadership role, other powers, such as China, can potentially take the US’ place in the clean tech economy. The US’ withdrawal can also have effects in terms of climate finance. For example, the contribution that the US was providing to the global south could be further reduced due to the changed political landscape, and undermine the achievement of conditional NDC pledges.

What is the role of art. 6 in meeting the Paris Agreement’s objectives?

Art. 6 of the Paris Agreement promotes international cooperation to achieve global emission reductions through cooperative approaches, which include carbon market and non-carbon market approaches, to promote ustainable development and poverty eradication. Under article 6 paragraph 4, countries can voluntarily use credits from emission reduction and removal projects towards the achievement of their NDC objectives. If recognised by its NDC, a Party to the Paris Agreement can buy carbon credits to fulfill its climate target. To ensure overall global emission reductions, it is essential that credits are aligned with the Paris Agreement and have a structured governance in place. The Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM) set up by article 6, paragraph 4, identifies opportunities and channels funds between the buyer and the host Party. This mechanism is also meant to replace the preexisting Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) created by the Kyoto Protocol. While the CDM had similar theoretical foundations, it has been subject to several criticisms over the years due to irregularities in its implementation. Considering the possibility to transfer 1 billion CDM credits to the new mechanism until the end of 2025, the efficacy of these credits is still being discussed at the time of writing. However, several types of carbon credits can be used, which vary greatly in quality and environmental integrity, and new credits are more qualified and reliable than in the past. Moreover, the monitoring mechanisms have evolved in recent years, and if MRV systems are put in place, credits could represent a valuable tool to avoid costly emission reductions in Europe while contributing to addressing GHG emission reductions worldwide.

Photo by UNclimatechange