Every year, the Italian government spends billions of euros on measures that directly or indirectly incentivise activities with negative environmental impacts, known as “environmentally harmful subsidies” (EHS). These subsidies are a structural issue in Italy’s economic policy and a major obstacle to the green transition.

But what exactly are these subsidies? Why do they exist? Can they be reformed – and if so, how?

What are Environmentally Harmful Subsidies?

The World Trade Organization defines a “subsidy” as any financial transfer by a public authority to a private entity. Subsidies can take the form of direct transfers, tax breaks, the provision of goods or services at a reduced cost, or price and income support.

International organisations such as the OECD and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have developed slightly different approaches for identifying EHS. While definitions vary, they share a common principle: EHS are economic subsidies that distort the way final prices reflect true costs and are granted in support of polluting activities.

For example, the OECD defines an environmentally harmful subsidy as any measure that encourages an increase in production levels through an increase in environmentally harmful activities – such as over-exploitation of natural resources, higher waste generation, or increased pollution – compared to a scenario where such a subsidy is absent. The IMF, meanwhile, adds another layer of analysis by distinguishing between explicit subsidies (direct public transfers and measures that make the retail price lower than the cost of fuel procurement) and implicit ones (the absence of adequate taxation of negative externalities, such as climate and environmental damage, health impacts, mobility-related externalities such as road congestion and accidents).

In Italy, an initial mapping of EHS was carried out by the Ministry for the Environment in 2015 (now MASE). Every year, MASE is required by law to publish a Catalogue of Environmentally Harmful and Environmentally Friendly Subsidies (EFS). This Catalogue is an essential tool for monitoring public spending and its environmental effects. It distinguishes between direct EHS and EFS (public resource transfers) and indirect ones (such as tax exemptions or differing tax treatment of similar products).

The burden of EHS on Italian public finances

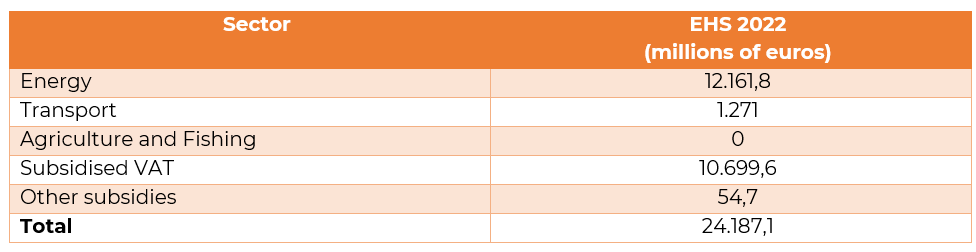

According to the most recent Catalogue published by MASE, based on 2022 data, over 24 billion euros was spent on EHS in Italy, of which 17 billion euros was used to support fossil fuels.

This figure marks a 15% increase compared to 2021, partly due to measures adopted following the Russia–Ukraine conflict. Over the same period, EFS increased by just 2.5%. This highlights how, at a time of geopolitical and energy crisis, rather than investing in its own energy security and independence through renewable energy, Italy subsidised imported fossil fuels – thereby increasing its dependence on third countries.

MASE’s estimates are conservative. In fact, depending on the definitions of EHS and the calculation methodology used, figures can vary substantially. The IMF, for example, estimates that including implicit subsidies (such as inadequate taxation of negative externalities of a given activity) would bring Italy’s total EHS spending in 2022 to 63 billion euros – 2.8% of national GDP. Legambiente estimates that in 2023, the amount spent on EHS may have reached as much as 78.7 billion euros, of which around 26 billion euros could be eliminated immediately with minimal social impact.

In its analysis, MASE categorises EHS and EFS by sector, revealing that nearly half of all EHS in 2022 were allocated to the energy sector.

These figures demonstrate that the Italian state economically supports production and consumption models that are incompatible with climate, security and energy independence goals. This, in turn, significantly reduces the already limited fiscal space available at its disposal.

What is (and isn’t) considered an EHS?

Not all subsidies linked to fossil fuels or polluting sectors are automatically classified as environmentally harmful. The classification is complex and depends on the context, use and impacts of the measure: for these reasons, MASE clarifies that the Catalogue is not exhaustive.

In particular, the Catalogue does not systematically include subsidies it defines as “implicit” – those subsidies resulting from the differing tax treatment of similar products and which may encourage the adoption of more or less polluting solutions (MASE’s definition of an implicit subsidy differs from the IMF’s.)

The tax differential between diesel and petrol is listed as an EHS, amounting to 3.157 billion euros in the latest version of the Catalogue. Recently, Legislative Decree No. 43/2025 was published in the Gazzetta Ufficiale, calling for the gradual alignment of excise duties on diesel (currently lower) with those on petrol over the next five years– a measure that goes directly towards correcting a structural EHS. The resulting additional revenue from this alignment will be allocated to the fund for local public transport and to the fund for the implementation of the tax delegation mandate provided for by the legislative decree.

However, there are other implicit subsidies that are not officially classified as EHS, even though they effectively are in terms of their impact. One key example is the difference in tax and parafiscal charges applied to electricity and fossil fuels. In Italy, electricity is subject to higher taxation, system charges and costs of emission allowances under the EU Emission Trading System compared to gas, diesel or petrol. This imbalance raises the cost of electric solutions, discouraging the electrification of consumption in the residential, industrial and transport sectors – a crucial step in reducing emissions. Despite this, the imbalance is not recorded among EHS in the official Catalogue, highlighting a limitation of the current classification methodology.

The absence of a clear, binding legal definition of EHS, at the national but especially at the European level, makes them difficult to identify – which is the first necessary step toward their elimination and reform.

How can EHS be reformed?

Italy has committed to reforming EHS in international (Agenda 2030, G7, G20, COPs, the EU’s Eighth Environment Action Programme) and in national forums. The National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) sets out targets to reduce EHS by 2 billion euros by 2026 and 3.5 billion euros by 2030. These targets are reiterated in the 2025–2029 Medium-Term Structural Budget Plan, which stresses the importance of recovering these resources to reduce the loss of revenue from environmentally harmful tax deductions.

Although the Catalogue is updated annually, there is still no comprehensive operational strategy for reform. The National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP), the primary tool for proposing an exit strategy from EHS, merely lists a handful of “inefficient” EHS amounting to less than 2 billion euros, without outlining a methodology for systematically identifying EHS and a socioeconomic impact assessment of their possible elimination, or a medium to long-term path for reforming them.

Reforming EHS is both necessary and feasible, but it requires:

- A comprehensive plan: the reform of EHS cannot be isolated from wider fiscal and economic policies and must be part of a broader package that includes measures to support decarbonisation and tools to protect the most vulnerable. Not all EHS can disappear overnight: some can be retained temporarily, but only within a clear reform plan aligned with climate goals and with a defined expiration date.

- Cost–benefit analysis: to understand the economic, environmental and social impacts of their eventual removal. Broad, non-targeted subsidies should be removed first; those based on the income or vulnerability of beneficiaries, more slowly and with greater caution. At the same time, alternative measures that are fiscally sustainable in the medium and long-term should be put in place to support the transition.

- No-regret actions first: the first step is to identify the subsidies that are easier to eliminate, those that are costly, benefit only a few, or are regressive – favouring large companies or higher-income groups. Simultaneously, reforms should prioritise sectors where low-emission alternatives already exist. Where such alternatives are lacking, or where the elimination of EHS would cause particularly negative social impacts, a more gradual and targeted (yet still aligned with decarbonisation goals) approach is necessary.

- A participatory process: EHS reform must involve all stakeholders: workers, businesses, public authorities and citizens. A broad and well-structured social dialogue is key to building consensus and overcome resistance.

Photo by Kasia Derenda