On 22-23 June, the French Government under the leadership of President Macron will host the Summit for a new global financing pact in Paris. The goal is to build a new pact between the countries of the global North and global South to address climate change and development needs. Today, the financial barriers of Global South countries are significant and unsustainable.

The Summit will take place at Palais Brongniart with over 30 confirmed Heads of State and Government, including Brazilian President Lula, German Chancellor Scholz, and European Commission President Von der Leyen. Over a third of the attending leaders will be from African countries. More than 30 official events will take place. US Secretary of Treasury Janet Yellen, Chinese Premier Li Qiang, the new President of the World Bank Ajay Banga, and UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres will also attend. The summit is supported by a Steering Committee and four working groups to address the following issues:

- ensuring greater fiscal space for the most affected countries;

- increasing private sector financing in low-income economies;

- increasing investments in green infrastructure;

- developing innovative solutions to provide additional resources to support countries that are most affected by climate change.

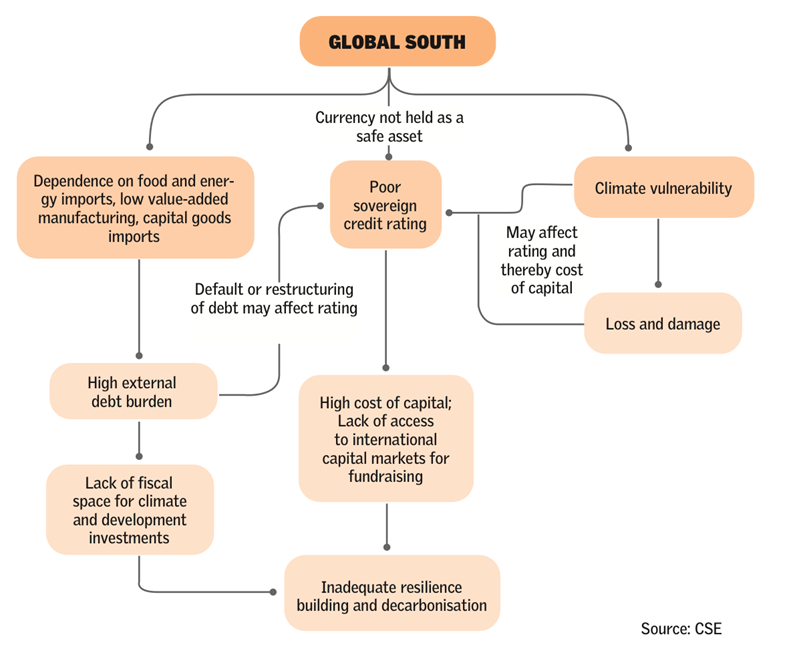

The Summit takes place in a context characterized by “polycrisis”: the slow recovery from the pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its direct consequences on food and energy prices, soaring inflation rates, the growing debt crisis, and intensifying climate impacts. These shocks have exposed the vulnerabilities and limitations of a global financial architecture, which is inadequate to meet the challenges of our time. In this regard, last May, the UN Secretary General presented a clear roadmap for reforming the international financial system and a call to the international community to make finance “resilient, fair, and accessible to all”.

The Paris Summit can signal a new political will for change and galvanise in particular G20 countries and the leadership of the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) for the necessary reforms. The Summit should initiate the rebuilding of the lost trust between the North and the South in a credible way.

Italy’s participation, ideally through President Meloni – who will be in Paris in the days immediately before the Summit to support Rome’s candidacy for Expo 2030 – would send an important signal ahead of the Italian G7 Presidency in 2024 for three main political reasons. The first is geopolitical. At a time when new and old powers, such as China and Russia, are gaining ground in Africa precisely through financial leverage, Europe cannot lag behind. The second is a question of security and development. Only by putting all countries in a position to respond to the various crises and have access to the financial resources for their sustainable development can the conditions for pursuing common security and prosperity goals arise. Finance should become a central lever of Italy’s upcoming investment plan for Africa (Mattei Plan). The third is a question of credibility. The recognition of Italy’s political leadership comes from being present in key moments and setting out a vision and concrete proposals for action. For a leading role of Italy on the international stage, the first step is to be there.

There are four policy areas in which Italy could make a difference globally and play a leading role in:

- Providing immediate liquidity for ongoing crises, also with respect to past promises. For example, Italy could reconfirm the G20 collective promise to redistribute $100 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to the poorest countries. Italy has already rechanneled 20% of its SDRs and could commit to reaching 30% (Japan and France recently committed to 40%), directing the additional quota to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Resilience and Sustainability Trust or to MDBs (there are ways that can clearly satisfy and overcome the concerns expressed by the ECB in this regard). Another example of pledges made by Global North countries but not yet fulfilled is that of reaching $100 billion per year for climate finance for Global South countries (promised for 2020). In this context, President Meloni could set out how she intends to use the new Italian Climate Fund, managed by the Italian DFI Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP). The Fund was launched at COP27, with a firepower of €840 million a year until 2026. President Meloni could commit to raising it to €1 billion a year with the next Budget Law.

- Developing innovative solutions to provide additional resources to support countries most vulnerable to climate change. This could be done through an emissions levy for maritime transport set by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) together with an ambitious decarbonisation target for the sector. In this regard, it is important that Finance Ministries do not oppose the proposal developed by France and the Marshall Islands (since it could be a tax that is beyond the Ministries’ control).

- Asking for and achieving a gradual increase in resources of the MDBs by inviting them to submit plans by October for a capital increase that would better support the most fragile countries, even by expanding the scope of funding and the access to concessional resources to all countries affected by climate impacts. MDBs should be invited to formulate plans that incorporate physical and transition risks into their resource allocation frameworks, increase the use of guarantees, and present a means to reduce foreign currency risk premiums on green and climate-resilient investments. Furthermore, countries like Italy should invite MDBs to collaborate with national development banks, such as CDP, to accelerate the creation of a pipeline of projects. Finally, Italy could commit to a new rapid and ambitious replenishment of loans and grants from the International Development Association (IDA), the part of the World Bank that makes concessional loans, with a commitment to increase the share of grants by 50% compared with to 2021.

- Transforming the current architecture of sovereign debt restructuring. Addressing the debt issue is more urgent than ever, with 61 emerging markets and developing economies in or at risk of debt distress (whose debt restructuring would requie more than $800 billion). The biggest step forward would be to support, within the G20, an extension of the Common Framework for debt treatment to all climate-vulnerable economies, including middle-income countries. Furthermore, in parallel to Italy’s request for a reform of the European fiscal system through the Stability and Growth Pact, Italy should demand at an international level for debt sustainability analysis methodologies to include the full range of climate risks and investment needs for the energy transition (estimated at $1 trillion per year by 2025 and $2 trillion per year by 2030 for developing countries except China). In addition, the IMF and the World Bank should be invited to incorporate climate risks and investment needs into the debt sustainability framework for low-income countries, which is under review this year. MDBs should instead be invited to design a guarantee instrument to replace old debts for sustainability-linked bonds as part of a broader effort to provide debt relief to countries in debt distress. In this sense, G20 countries should institute a suspension of debt service payments for countries requesting its restructuring (debt service payments by low-income countries are at their highest level since 1998: for 91 countries these correspond to an average of 16.3% of government revenues in 2023). Finally, Italy could promote the use of clauses to suspend debt service payments when a climate shock occurs (climate-resilient disaster clauses – CRDCs). This would free up cash flow that could be better used to support relief and damage reparations. Italy should therefore ask all international financial institutions to incorporate CRDCs into their loan agreements.

In order to achieve concrete results and respond to the political rationale set out above, it is urgent to raise these issues – too often perceived as “technical” – to the highest political level. The presence of both President Meloni and Minister of Economy and Finance Giorgetti at the Paris Summit would provide strong political support for reforms and demonstrate Italy’s leadership and responsibility for the most urgent challenges of this century.

The Paris Summit could become a first step towards regaining the lost trust between the global North and global South. In any case, it will not be a final destination, but rather a starting point. In fact, equally important will be to take the outcomes forward throughout this year’s meetings, particularly in the run-up to the IMF and World Bank Autumn Meetings in Marrakech from 9 to 15 October. Until then it will be key to show the political will to achieve short-term goals and build consensus around a long-term agenda for reforming the rules and architecture of the global financial system. Political opportunities for further progress will be the Africa Climate Summit (Nairobi, 4-6 September), the G20 Summit under the Indian Presidency (9-10 September), and the Climate Ambition Summit during the UN General Assembly on 18 September. The Italy-Africa Summit, expected in the autumn, is also part of the political opportunities landscape of the coming months. Finally, this year COP28 in Dubai (30 November-12 December) can also send a clear signal about the need for a broader reform of the financial system to support a substantial increase in climate and nature funding in this critical decade to limit global warming within 1.5 degrees.