Read the policy briefing “The climate and security nexus in Italian foreign policy”

The start of COP29 in Baku, the upcoming COP30 in Belem, Brazil, and the approaching presentation of the updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) by the countries of the Convention in February 2025 make 2025 a real turning point for climate diplomacy. On the peace and security front, the Azerbaijani presidency launched the COP29 Climate and Peace Initiative, which has received the approval of several countries, including Italy, and confirms the need to promote further actions for the operationalization of concrete initiatives on the nexus between climate, peace, and security.

International actors are becoming increasingly aware of the interconnection between climate, security, development and peace, and are recognising the importance of integrating these dimensions into their global projections. Climate is playing an increasingly prominent role in the foreign policy strategies of various countries, especially in security and defence matters, as well as in the strategies established by international and supra-national organisations. In 2021, NATO adopted an ambitious Climate Change and Security Action Plan to integrate climate change considerations into the Alliance’s political and military agenda. As part of its 2022 Strategic Concept, NATO reiterated how the organisation “should become the leading international organisation when it comes to understanding and adapting to the impact of climate change on security”. Furthermore, since 2015 the G7 incorporates a commitment to achieving net-zero carbon emissions, and recognised climate change as an existential threat to security in 2022 with a joint statement issued by the Foreign Ministers of Canada, France, Italy, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom under the German leadership

At the European level, in 2023, the European Commission and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy issued a Joint Communication on the Climate and Security Nexus, which aims to establish the operational priorities around which various bodies of the European Commission and the European External Action Service (EEAS) can coordinate to ensure the climate-peace-security nexus is better integrated into the EU’s external policies.

As evidenced by this growing international interest, an organic, long-term, sustainable, and innovative foreign policy strategy cannot overlook the central role of climate, with particular attention to critical issues such as food systems, disaster prevention, crisis response, economic development, and migration flows. For Italy, this entails understanding the regional and transnational repercussions of climate risks within its national security concept, while also adopting a climate security perspective in monitoring developments, defining priorities, developing policies to prevent risks, respond to impacts, and establish partnerships.

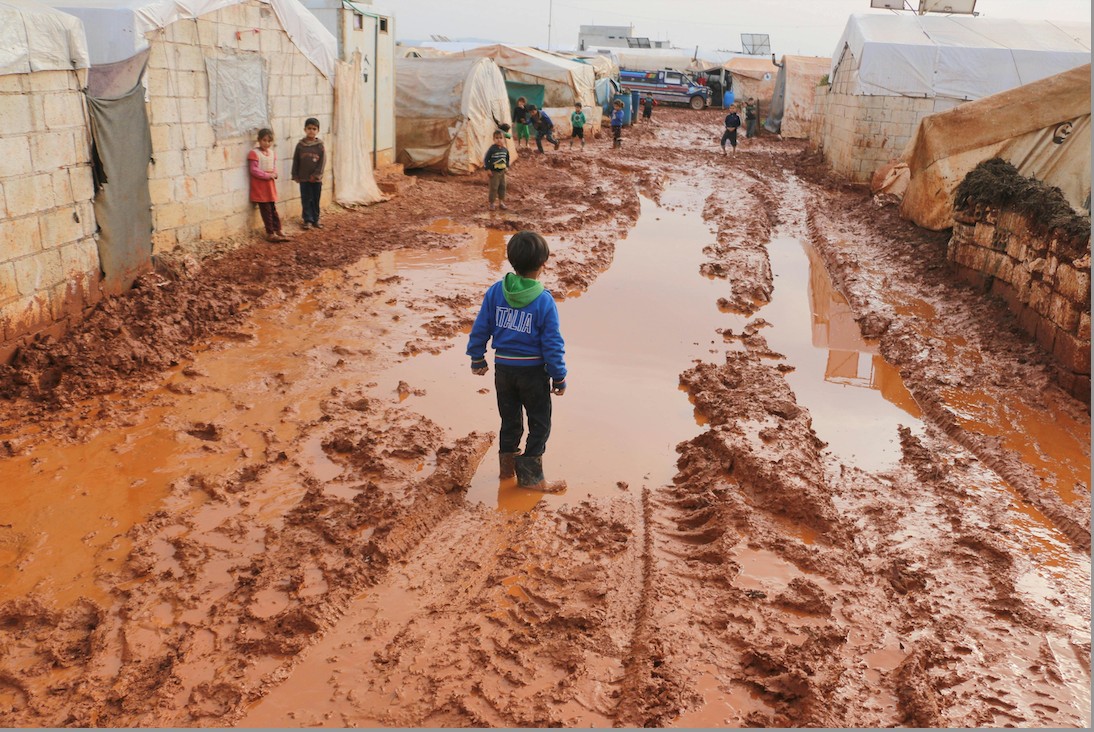

These considerations are even more urgent in a region highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, such as the Mediterranean, where cascading climate impacts risk undermining the success of cooperation efforts and, more generally, hindering the achievement of Italy’s and Europe’s foreign policy objectives. More specifically, in its efforts to build sustainable development on the African continent, the Mattei Plan should take into account that climate change is already contributing to reshaping migration flows. Once a hotspot for migration between North Africa, the Levant, and Europe, the Mediterranean Basin will continue to be a hotbed of migration across the African continent and Europe.

The Mediterranean Basin, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), is a climate hotspot, a unique geophysical region where climate change is occurring faster than global trends. Average annual temperatures have already exceeded 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, 0.4°C higher than the global average variation, even though the region accounts for only 6% of global emissions. The impacts of climate change—starting with average temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and increased extreme climate events—are already exacerbating vulnerabilities in the region. This evolving climate scenario has direct and indirect implications for the security and stability of the entire region, extending to political, social, and economic dimensions.

The Climate-Security Nexus in Italian Foreign Policy

It is crucial that the integration of a climate security framework in Italy’s foreign policy shifts from a reactive and short-term approach—focused on responding to environmental disasters and extreme events—toward a proactive approach that aims to anticipate and prevent the impacts of climate change on security, defense, economy, and finance. This preventive approach is necessary in planning resilience policies for the region with horizons for 2030, 2050, and beyond, defining Italy’s role as an actor in climate diplomacy and ensuring long-term coherence in foreign policy tools for managing slow-onset climate impacts, including water and food security.

Promoting a climate security framework must go hand in hand with promoting policies for adaptation to the impacts of climate change and a long-term vision for regional decarbonization. Investing in adaptation means also addressing the correlation between the impacts of climate change and human mobility.

Italy has enormous potential to become a key player in international climate policy: globally, due to its role in the G7 and G20, as a Member State of the European Union, and regionally as an actor in the Mediterranean. Therefore, it is urgent that Italy integrates the dimension of climate security into its foreign policy, committing to interventions that support building resilience in the countries of the expanded Mediterranean region. In this context, it is important that Italy takes advantage of the opportunity to make its institutions fit-for-purpose, capable of responding to a future of regional and global uncertainty, where climate and its impacts will increasingly become the fundamental and defining variable of geopolitical processes. To this end, it is necessary to rethink climate diplomacy and institutions by overcoming a fragmented approach and extending the climate agenda cross-sectorally:

- Integrating a climate risk management framework based on climate scenarios and the most up-to-date scientific data, with a particular focus on cascading climate risks that directly impact Italy’s system. Ideally, a climate risk map should include appropriate measures for building resilience and security based on projected climate impacts for surpassing the thresholds of 1.5°C, 3°C, and 5°C of global warming.

- Establish regular working groups and discussion forums with experts, international partners, and the private sector within Italy’s relevant ministerial departments (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Ministry of Defense, Ministry of the Environment and Energy Security), relevant Directorates-General, and the diplomatic corps, to increase capacity and awareness in identifying climate risks in specific areas of competence, and to review current policy tools by testing their effectiveness against climate risk. Given the systemic and horizontal nature of climate and its relevance to various policy areas, the working groups should identify critical areas, develop solutions, monitor institutional processes, and share best practices.

- Propose an inter-ministerial task force: a level of intra-governmental and inter-ministerial coordination is needed to enabling alignment between Italy’s relevant ministerial departments and the Prime Minister’s office, ensuring coherence and integration of foreign policy initiatives in line with the Paris Agreement’s climate goal, particularly the safeguarding of the 1.5°C threshold. This means ensuring that the risks, but also the opportunities, of the climate dimension, especially its impacts on security, are fully understood and represented.

- Integrate regional risk analysis and their cascading effects on the Italian system within foreign policy strategies, providing workable solutions and identifying governance gaps and concrete projects aimed at building resilience. In this regard, strategic and policy-oriented research can benefit from increased collaboration with centers of excellence, universities, think tanks, NGOs, and international organizations to develop further knowledge on climate risk monitoring, anticipation, and prevention. It is crucial to direct research towards the development of effective policies for managing climate risks.

- Prioritise clean energy partnerships with southern Mediterranean countries in foreign policy, focusing on decarbonization and diversification of economic systems, particularly relevant for fossil fuel-exporting countries like Algeria, Libya, and Egypt. Italy should support industrial strategies for the development of transition plans, to build economic resilience to shocks, including those related to climate.

- Support Mediterranean countries in redefining climate targets and encourage ambitious decarbonization targets: Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), along with National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), are strategic tools for the most exposed countries to receive support in appropriate multilateral contexts. Yet, they are still underutilized in Mediterranean countries or lack standardized benchmarks. An NDC, supported by an NAP, provides a roadmap for fully understanding the needs and development trajectories of each country, effectively redirecting cooperation instruments.

Read the policy briefing

This Policy Briefing was prepared by ECCO in partnership with the Paris office of the HeinrichBöll Foundation.

Photo by Ahmed Achaka